Recently, my friend and fellow homeschool blogger, Mary Prather, wrote about the benefits of giving (or allowing) our children to have an anchor, an activity that they go to to center themselves, to fill time, to find peace, to find challenge (“Give Your Child an Anchor”, Homegrown Learners, December 10, 2012).

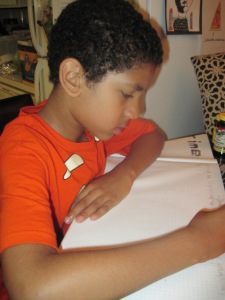

My youngest child is an avid writer. And when I mean writer, I don’t mean he cranks out stories (although he does write stories). I mean, he writes everything: steps to designing a chicken coop in Minecraft; graphic novels about Batman and Star Wars characters; “chapter books” about famous battles; bios of superheroes he invents. Unlike what happens in most public school classrooms, where kids only write fictional narratives until grade 3 (because it’s on the state test), then they switch to biography (because that’s on the grade 4 test), then on to persuasive essays (you get the picture), he learned, from an early age, that writing was putting pen (or crayon, or marker, or paintbrush, or keystroke, or all of the above) to paper to communicate. And he simply loves to write in every way that you can.

I don’t have any trouble getting him to write. In fact, early on in our homeschooling of him, we learned to just leave him alone, and be resource providers. We got more mileage out of introducing him to a new genre of writing, and analyzing its features, then by forced writing lessons. No bueno. But I know that many homeschoolers (and public school teachers!) struggle to get kids to write, and I really believe it’s because we 1) limit what “writing” is and 2) don’t give kids interesting things to write about (or read about, or talk about, for that matter) in most schools.

Here is my list of ten things that all kids (from preschool to high school) should know how to write, to be complete writers, and my rationale for each:

- An organized list

- An email

- A business letter

- A hand-written thank you note

- A poem or lyrics to a song

- A personal or fictional narrative

- A written argument

- An informational article

- A photo caption

- The directions for a task or activity

1. An Organized List…

A list is probably the last thing people think of when they think of writing, and it’s the kind of writing I do most, and do absolutely every day. Creating and using lists teaches kids so many things:

- Goal-setting & progress monitoring

- Accountability

- Prioritization

- Time allocation

From an early age, my son learned to use a checklist to keep track of his homeschool work and chores. He feels accomplished crossing things off, tends to get less sidetracked by less important distractions, and gets more done!

2. An Email…

Nowadays, most companies prefer that you contact them by email, and even public school teachers use email to communicate with their students. Judging from the amount of time companies spend on teaching their employees email “etiquette,” it seems that, as a writing form, it deserves its own instruction:

- Knowing your audience

- Writing subject lines that enable you to search your mail better

- Keeping things focused on one topic

- Responsible use of copy, blind copy, reply all, forward, recall and other functions

- Attaching or embedding additional information

3. A Business Letter…

Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1839) wrote that “the pen is mightier than the sword.” In these days of email, cell phones and Twitter, customers often neglect the most powerful tool they have to communicate with businesses: the letter.

When kids learn how to write a business letter, they learn some important nuances of language:

- How to use a formal tone in writing

- Putting the most important points first (in case the whole letter isn’t read)

- How to use the “compliment sandwich:” open nicely, get to your issue, then wrap up warmly

Look for opportunities for your kids to practice writing to a company or organization, in homeschool or classroom.

4. A Thank You Note…

When I was little, of course we didn’t have computers or cell phones. My mom made us write thank you notes when we received gifts. They didn’t have to be works of art, but they WERE written. The end. Here were her reasons (and they are mine, too!):

- Manners, manners, manners!

- Everyone loves to get real mail (don’t you?), written by someone, and addressed to someone by hand. On paper. With a stamp.

- Gratitude is something we all need to practice.

In short, thank you notes are mostly about the feelings of the other person, and have very little to do with us.

In my third grade classroom, I had a letter writing center, where students practiced letter format and wrote letters to students and staff in the building. Once a day, the mail carrier would deliver the mail, putting letters into classroom “mailboxes” (folders tacked to the bulletin board), and hand delivering mail that went outside the classroom. We were the talk of the building!

5. Poetry or Song Lyrics

One of my favorite writing pieces from my youngest son’s preschool days was a “song” he wrote. It had preschool words, and music notes, and was written on yellow construction paper, and, when asked to sing it, he sang it the same way each time. He still likes to write songs and raps, and perform them.

Writing forms like poetry and songs, teach important writing ideas:

- Powerful word choice: since the author can only use a few words to convey a big idea;

- Visualization and elaborative detail;

- How to create a mood using the words or formation of the text;

- The connection between art, music and words when conveying a message.

For many kids, analyzing song lyrics works when poetry study does not, because the text is relevant and familiar to them.

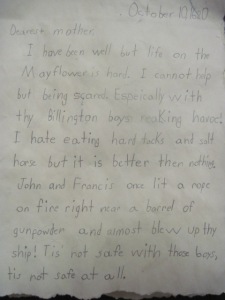

6. A Narrative…

I will be the first to admit to any child, that writing fictional stories is NOT my strong suit. I am great at personal narratives, and love to spin a yarn (usually at the expense of my family), however.

Whether fictional or based on real-life events, it is important for kids to learn how to tell a story. Story-telling is an ancient art form, and serves many social and literary needs, and teaches many things:

- How to build a plot where the action rises and falls;

- The importance of setting, character development and elaborative detail (even in true accounts);

- How to set a tone (humor, drama, reflection)

When my eldest son moved into a new apartment a couple of years ago, he found a box with things from his little boy days, including a family favorite, My Vacation Journal, written when he was five. It had “chapters” such as “Uncle Andy with Vacation Hair,” “The Vicious Frog Day,” and “One Day When I Was Fly-Fishing.” It was written in all caps, and had more exclamation points than anyone needs in one writing piece. We sat in my backyard, and loved it all over again.

7. An Argument…

So here’s a type of writing that has important life implications, whether trying to convince your dad to buy you a new bike, applying for a summer job, or completing a college application.

Here are things this type of writing teaches:

- How to clearly state your position

- How to back up your position with real evidence (not your opinions)

- How to evaluate and then choose the best evidence to support your position

- How to anticipate alternative views and prepare for them in your argument

Not that we wish to abdicate all parental decision-making, but it’s really hard to resist a well-crafted argument when your kids bring it to you!

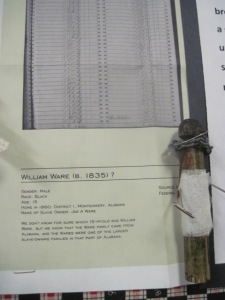

8. An Informational Article…

I mean, more than that old chestnut, the animal report. If you look over your mail table or coffee table, you probably see more informational text than fictional pieces. A lot of the “heavy lifting” of the informational text genre comes before the actual writing:

- Engaging Topic – What would I like to write about? What would people like to read about? What are people already writing about?

- Inquiry – What would I like to/need to know about this topic? What is already written?

- Research – What is good source material? How do I evaluate sources?

- Format and Structure – How does the format of my piece also teach?

My first full year of homeschooling my youngest son, he wanted to learn about military helicopters. We spent countless hours on You Tube, watching videos of different classes of helicopters, reading about the history of the helicopter industry right here at Sikorsky, in our home state of Connecticut, and learning about the different branches of the US military. He learned things through his research that he still treasures, today.

9. A Photo Caption…

Last night, my youngest and I were working on a blog article I was writing on interactive bulletin boards as a center (he was providing over-the-shoulder commentary and feedback on my work), and we began talking about what to put in a caption of a photograph. We covered a lot of territory in two sentences:

- Summarization

- Creating “stand-alone” visuals

- Proper use of the “snipping tool” and other photo-capture tools

- Proper citation for images and photos

- Non-fiction text features

- Choice and placement of graphics, including their captions

- Attributions and copyright laws

My son uses screen captures and the “snipping tool” all the time, but never realized that you can’t simply place someone else’s photo in your PowerPoint without properly acknowledging its creator.

10. The Directions for Doing Something

My middle son is a lifelong Lego-Maniac. Even as an adult, he uses the excuse of having a little brother who is 14 years his junior as an opportunity to drag out his collection of Legos and build. All those years of following directions had a direct effect on his comprehension of procedures, however, and he has the ability to carefully explain directions to his crew at work, as a result.

Writing step-by-step directions is a text form not seen much in most social studies and English courses, but an integral part of mathematics and the scientific method. Writing a procedure helps students:

- Break a complex task down into important sub-tasks;

- Think logically and hierarchically;

- Anticipate reader confusion and address it ahead of time;

- Learn how to efficiently incorporate diagrams or illustrations to clarify

Unlike the narrative, which tickles the right side of the brain, lists and procedures are a natural for left-brained thinkers.

Conclusion

Whether journalers, notebookers, traditional note-takers or “each class in its own pocket” teachers, the 10 Writing Pieces outlined above can be incorporated into any writing curriculum. Looking over my list of 10, I’m wondering what would happen to our writers if we focused on each one of these for an entire month. By the end of the 10 month school year, what kind of writers would we have?

I think we’d have good ones.

Related articles

- 10 Tips on How to Write a Better Business Letter (dricefreelancewriter.com)

- Children’s Author Presents Free Seminar on Writing to Homeschoolers (prweb.com)

- A Beginner’s Guide to Homeschooling (education.com)

- Rules of Writing # 51 : Take a Walk Around the Block (stepintothecruz.wordpress.com)

- Long Story: The Writing Process (dysfunctionalliteracy.com)

Thanks for the ping-back! Have a wonderful weekend! ~ Kim